The 38th edition of the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), ran from November 13 to November 23. It was the first festival under new Artistic Director Isabel Arrate Fernandez. As usual, IDFA was a veritable feast of the world’s best creative documentaries.

The 2025 film lineup reflected our current global climate of insecurity, from bearing witness to ongoing violent conflicts, including Gaza and the Ukraine, to the plight of individuals displaced by political turmoil.

At the same time, there were films that provided space for reflection and healing, stories that highlighted the transformative power of art, and docs that urged us to stay open to alternative perspectives. Here are five highlights from the International Competition that provide a snapshot of IDFA’s programming this year.

IDFA

IDFA

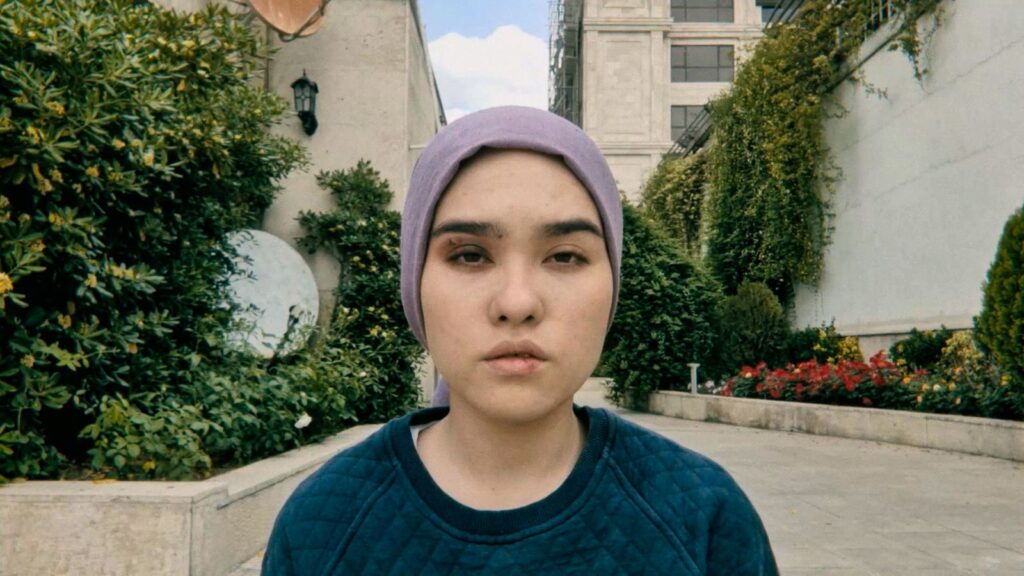

A Fox Under a Pink Moon

Veteran Iranian filmmaker Mehrdad Oskouei’s latest film, which won Best Film in IDFA’s competition, is a migration story of a young asylum seeker trying to reach Europe with a twist: There was no film crew. Mehrdad directed the entire film remotely. And the protagonist, Soraya Akhalaghi, filmed herself using two cell phones over five years. (Akhalaghi receives a co-director credit.)

Oskouei was first inspired to try this novel approach several years ago when he viewed some precious “raw” footage that the protagonists of Sunless Shadows (his film about teenage girls in a detention centre) had shot of themselves when they were on their own.

Akhalaghi has always lived in Iran. But as an artist—and as a woman—she is determined to seek a better life. “I am a ‘gamer’ I won’t fall off the edge of life,” she states, referring to the code word for crossing a border illegally. Via Soraya’s cell phone recordings, we witness harrowing scenes of her and fellow asylum seekers’ repeated attempts to cross the border from Iran to Turkey en route to Europe.

But beneath that bravado, there is a young woman who has grown up with little parental care and who is married to a man who beats her. Soraya deals with constant feelings of intense fear and loneliness by creating her own world with coloured pencils, markers, and papier mâché.

We are soon immersed in Soraya’s inner life through drawings of a fox (her loyal travelling companion), a moon that watches over her, and her alter ego, a clown with hollow eyes and a sewn-up mouth. Many of these drawings, reminiscent of Frida Kahlo’s macabre imagery, are brought to life via animation.

A Fox Under a Pink Moon is also interspersed with scenes of television news regarding Afghanistan. Although she was not born or raised there, Soraya considers the country of her ancestors to be her homeland. For Soraya, Afghanistan is not merely a geographical region. It is a dream space that she needs to believe in to stay grounded. The Taliban takeover of this country following the American evacuation disturbs her and Soraya knows that she needs to “find another homeland.”

Soraya is extremely bright and willing to take incredible risks. Will that be enough to help her cope with the trials of undocumented migration? The process of making video recordings, which she addresses to “Uncle” Mehrdad, will certainly play an essential role in her journey.

IDFA

IDFA

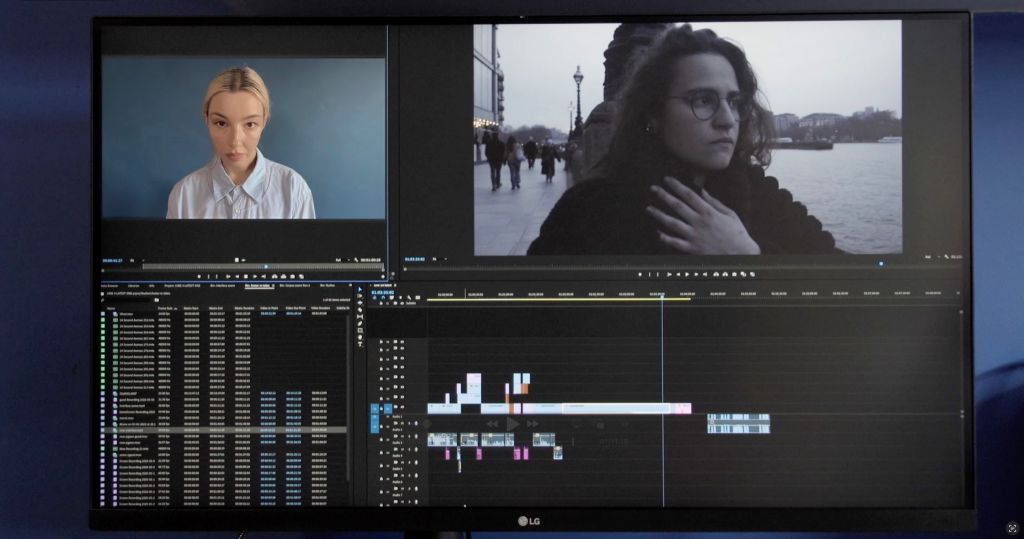

Synthetic Sincerity

Marc Isaacs’s Synthetic Sincerity is a playful but pointed look at the brave new world of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) that we are hurtling towards.

Isaacs, a singular filmmaker who has made a career of probing the political and social fabric of British society through offbeat documentary films, is starting a new chapter of his career with this film. Discouraged by an increasingly risk-averse doc industry and determined to “keep his freedom as a filmmaker,” Isaacs has turned to hybrid filmmaking. Synthetic Sincerity is his third docu-fiction.

As in The Filmmaker’s House and This Blessed Plot, Isaacs’ latest film features non-actors playing versions of themselves in fictitious scenarios. All three films are written by Adam Ganz.

The adventure begins as Isaacs agrees to license his body of film work to a lab “where data learns to be human” in exchange for documenting the lab’s working process. An attractive and well-spoken A.I. avatar guide cheekily ensures Isaacs that the lab researchers will be delighted to work with an old school doc maker like him.

As Isaacs innocently tries to understand the A.I. work underway, one of the characters, who can quote Robert Bresson, tells Isaacs that she used to work in film but now she wants to be where the future is.

The controversial use of generative A.I. technology is cleverly alluded to as Lynn, one of the researchers, records Ablikim, a Uyghur man, pronouncing key phonemes in English and his mother tongue. The lab needs these audio recordings in order to create an A.I. version of Ablikim that will be able to express emotional truths — that the stoic real-life Ablikim cannot. They will give a voice to the voiceless.

At one point, Isaacs is continually interrupted by the avatar. When he refers to “her” rude behaviour, she snaps back “Don’t expect ethics from me, Marc.”

Synthetic Sincerity leaves us with overwhelming questions. What is an authentic image in an A.I. world? What will happen when film loses the power to document? Can our memories be colonized?

IDFA

IDFA

Flood

Katy Scoggin’s Flood, is a personal account of the ongoing clash between science and evangelism in the United States. The film marks Scoggin’s feature directorial debut after spending six years working with Laura Poitras, including as director of photography and co-producer for the Oscar-winning Citizenfour (2014). Poitras is among the executive producers of Flood.

While filming with paleontologists in the badlands of western Kanas, Scoggin was tempted to tell her father Marvin (a primary school science teacher) about the remarkable fossils that were being uncovered. Yet, at the same time, she knew that his religious beliefs would make it impossible for her to fully explain the discovery of the fossils. Marvin is a young-earth creationist who genuinely believes that all of the earth’s creatures are descendants of animals housed on Noah’s Ark.

When Scoggin decides to use her professional filmmaking tools to try and reconnect with her father, the ten-year development journey of this film is set in motion. It’s an incredible challenge. Although the filmmaker loves her father, she has not had any significant conversations with him since abandoning the oppressiveness of her conservative Christian childhood.

When Scoggin returns home, she discovers that several of her relatives have also moved away from a literal interpretation of the Bible. During a family outing to the Grand Canyon, her nephew openly challenges the guide from Canyon Ministries, a faith-based tour company, for providing a creationist explanation for the fossilized sea creatures in the area. This situation complicates Scoggin’s attempts to reconnect with her father. As other family members carve their own paths, Marvin takes refuge behind the fortifications of his beliefs.

IDFA

IDFA

Silent Flood

Golden fields of wheat swaying in the sun, children laughing as they play on the shores of a placid river, a horse and carriage passing through a lush tunnel of leaves—the long, painterly scenes of Silent Flood are so idyllic, that they hardly seem real.

However, this farming community in western Ukraine does exist. And it exists because it has found a way to survive ongoing existential threats. Periodic flooding of the Dniester River and destructive military campaigns are regular occurrences in this part of the world. They’re so inevitable that they serve as markers of time.

Bridges built by the Austro-Hungarian empire have long since been destroyed by natural forces and retreating armies. The villagers now use a ferry to travel across the Dniester River as a result. The detritus of warfare, including landmines, lies hidden in fields and forest. The villagers have taught therefore their children to avoid certain areas.

This observational film by Ukrainian director Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk is a testament to the gentle resilient ways of the Saved Ones, as they are known locally. Similar to the North-American Amish, this Christian community has stayed true to its 19th century roots. It shuns modern technology, drinking, smoking, and anything else that might distract them from their focus on worship.

It is also a pacifist society that does not send its sons to battle. In a country that has been at war with Russia since the February 2022 invasion, this is not a popular position.

Via voice-over narration, we discover how members of this community view themselves and also how they are viewed by outsiders. One voice quips “Maybe they are the saved ones!!!? Because they don’t die in battle.”

Silent Flood is plea for understanding. The Saved Ones may not send their sons to war, but they have found other ways to support their fellow Ukrainians. Their simple way of life, rooted in kindness and non-violence, holds lessons for us all.

IDFA

IDFA

All My Sisters

Massoud Bakhshi began recording footage of two beloved nieces when then were toddlers. Initially, he planned to continue filming until they turned seven years old and started school. However, this family project became so engaging that he decided to keep filming for 18 years. The result, All My Sisters, is an extraordinary account of growing up as young women in Iran.

Public and private spheres are kept extremely separate in Iranian life, so Bakhshi makes consent part of the film structure. In the opening scene of, Bakhshi requests his nieces’ permission. Throughout the film, we view the young women watching themselves as they develop from young children to their current selves. Periodically, the film pauses as Bakhshi asks them to comment on certain scenes.

As young children, the girls are completely carefree— giggling in the playground, watching cartoons and blowing out birthday candles. Before long, their traditional and deeply religious grandmother begins to teach them about the meaning of sin, Hell, and mahram (people who are allowed to see your hair and body contours). The little girls are not overly concerned. When she is scolded by her granny for dancing and told “a reader of the Quran would not do that,” her granddaughter plainly replies that she is not a reader of the Quran.

As the nieces start school, they seem pleased with the novelty of their chadors, which enable them to resemble their older female relatives. And their play-acting reflects their traditional milieu, they recreate scenes involving inquisitive morality police.

Years later, though, as they become teenagers, the nieces begin to openly question Iranian government policies and they join protests along with their friends. Their mother and grandmother plead with them to focus on their personal lives. “How is your anger useful? It only drains your energy,” the girls are told. The girls refuse to ignore horrors in their midst and we view them chanting “Woman Life Freedom” from the rooftops with their peers.

Bakhshi did several pre-edits over the years in order to keep track of the vast amount of footage. Remarkably, the total editing time was only nine months. As their uncle, Bakhshi is clearly impressed by the girls’ courage and humanity. At the same time, as an Iranian artist, he is all too aware of the potential dangers that await Iranians who are too outspoken.

***

Here are some additional highlights from IDFA 2025:

IDFA

IDFA

Memory

Memory is the debut feature documentary of Ukrainian-born artist and filmmaker Vladlena Sandu. This eclectic heartfelt account of Sandu’s formative experiences is about memory, political indoctrination, and the transmission of violence.

Via surreal theatrical sets, recreations acted by children, archival footage, and a poignant personal narration, we learn about Sandu’s childhood and early teenage years during a time of great political turmoil, including the collapse of the USSR and the fracturing of the Chechen Republic. The soundtrack to this singular documentary draws from an extremely wide mix, ranging from “Prokofiev” to Bob Dylan to Dr. Alban’s pop hit “It’s My Life” to themes from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

A sensitive child who is simply trying to make sense of her world, Sandu wonders why she has been sent to live with her severe and mean-spirited grandfather and her superstitious grandmother. She also wonders why her teacher wants her to emulate Lenin. But Sandu’s innocent questioning leads to punishment more often than it leads to answers.

Sandu was barely a teenager at the beginning of armed conflict in the Chechen Republic. In a heartbeat, her simple life in Grozny was turned upside down. All family, friends and neighbours lived in fear of brutal attacks—whether they were Russian or Chechen— and there were extreme food shortages. While the tone of the film becomes increasingly grim, her story continues to be told using Barbie dolls, action figures and other children’s toys.

IDFA

IDFA

Kabul, Between Prayers

This sympathetic portrayal of a Taliban soldier and his family urges us to consider the reality of life for young people growing up in Afghanistan. In a country that has been decimated by decades of foreign military intervention and stripped of its cultural heritage, this film asks if it is any wonder that some young men heed the siren call of religious soldiery and glory in the afterlife.

Kabul, Between Prayers is Afghan-Dutch director Aboozar Amini’s second film in a planned trilogy about the Afghan people who “keep paying the price” of being caught between superpowers. His acclaimed debut feature, Kabul, City in the Wind, opened IDFA 2018.

Thanks to extraordinary access, developed over years by Amini, Kabul Between Prayers tells the story of Samim, a Taliban soldier, in all aspects of his daily life: guarding a bridge checkpoint with his M-16 assault rifle, praising recent martyrs with fellow Taliban, playing outdoor games with his younger brothers, and seeking advice regarding his strained marriage from both his father and his spiritual adviser.

Amini is Hazara, an ethnic group that has suffered terribly under the Taliban. However, Amini, who grew up in his father’s Kabul bookstore, is able to take an authentic interest in Samim’s life because he believes that the only way forward is telling true stories and looking for shared humanity. “Whether human (qualities) or radicalization, I just try to catch the reality of them,” Amini said during a Q&A following the film’s IDFA premiere. It’s a welcome philosophy for a festival that shared a multitude of realities this year, not matter how harrowing, provocative, or radical they may be.

The post A World of Creative Documentaries at IDFA 2025 appeared first on POV Magazine.